František „Čuňas“ Stárek, born in 1952, was a dissident, a signatory of Charter 77, and a leading figure of the Czechoslovak underground. In 1979, he co-founded the cultural samizdat periodical Vokno. Together with colleagues Pavel Lašák and Jiří Včelák, they established a 'samizdat research institute', where they experimented with new technologies, including 8-bit microcomputers. After the revolution, he worked at BIS and currently works at ÚSTR.

FS: Tigrid sent me the Spectrum – by some route that I wouldn't be able to describe anymore. It was for sure smuggled from France. Anténa also had one. He earned the money for it working a temp job. It was an incredible amount of money at the time, about 11 thousand [crowns]. That was quite a sum. But surprisingly, quite a few people did it. I also knew Koula from Chomutov, he had the same computer. Suddenly, people started appearing who're working with it and own one. So we thought it could be the future of samizdat. It probably would have been, if the revolution hadn't happened. Samizdat would probably have moved to computers. It's incomparably easier to copy text files using a computer than to retype them. There were practically no copy machines at the time. If there were, it was a Rank Xerox, and those were completely inaccessible to ordinary people, and besides, each copy was terribly expensive. An A4 page cost about 5 Kčs. The Fotografia cooperative had them, but there were incredibly few in Prague. You could come and copy there, but it cost 10 Kčs. Fortunately, I knew a girl at Smíchov, where there was a Fotokino shop that had a copier. Viorika, our friend, worked there, and she occasionally did something for us. She couldn't do everything either – she could only do it when she was alone, and mainly she had to save up the cartridge so they wouldn't catch her with too few paid copies.

JŠ: What other technologies did you use?

FS: Samizdat started with carbon copies. But we mainly wanted to make a magazine, because we needed it to be for a target group that would regularly subscribe and read it and also respond to it. Classic samizdat relied on a chain reaction. Someone typed ten copies, gave them to others, and one of those ten or several of them got hooked. It also had the advantage of refining the quality of the book. Nobody typed something they thought was stupid. They always only copied what they liked and considered their own. I lived with samizdat for 15 years, and the most commonly reproduced novel was

1984 by Orwell. You could see all the techniques that were usable there. Past the typewriter came reproductions on the so-called OC ("ócéčko"). Building plans were made on that. The matrix was on tracing paper. From that, they made copies of plans on the OC machine. I remember when I worked as a surveyor at Metrostav, we had everything on these OC copies. It was kind of purple. The paper was special and it was steamed. It was exposed through the tracing paper, and where it was black, it didn't react, and ammonia vapors caught there, in which it was developed. It smelled terrible. When text needed to be copied like this, A4 sheets of carbon paper were made, put in a typewriter, and pushed through the machine, but to make them even blacker, black carbon paper was also placed against the paper to make it black on both sides. The ribbon did it from above and the carbon paper hit it from behind. I've even seen Orwell, again, done this way. But I never got into that because only someone who had it at work could do it. It was in various construction companies, but I never got access to it.

The first machine we had was a Ormig hectograph. There you also put carbon paper against it, write on it – it's better to write without the ribbon so the letters sit well, because the ribbon is still a kind of buffer. The hectographic carbon paper is coated with a thick, greasy paint, and it leaves a mark on that chalk paper. On the chalk paper is a matrix, which is then fastened into the machine and rotates on a cylinder. Before it's started up, there's felt that's a bit soaked with alcohol. Natural paper passes over it, so there's a film of alcohol on it, which slightly dissolves the paint on the matrix, which is usually purple. There were also black ones, but those were only available abroad.

The most important thing for us was the cyclostyle stencil. The most essential part is this sheet – fabric impregnated with wax. It was put into the typewriter like this and typed on without a ribbon. The letters then knocked the wax out of the fabric. So a hole remained in the shape of the letter. It was hard to type on, so carbon paper and a sheet were put behind it, on which it was written, so corrections could be made. When a correction was needed, the holes had to be varnished and pricked with a needle to make a new letter. All this was removed and the stencil was put into the machine. Paint was sent inside the machine, a cylinder rotated against another cylinder, and the pressure of the cylinders could be regulated. The cylinder pushed paint through the holes in the shape of the letters. There's this natural, porous paper that absorbed the paint well.

The numbers from the hectograph were about 120 copies maximum, because the paint on the matrix was being depleted. The cyclostyle also had its lifespan. The stencil would deform, then tear. From the cyclostyle, you could make a maximum of about 500 copies.

JŠ: How did it start with computers?

FS: We knew that dot matrix printers could be connected to them. The first thing we thought of was to put a cyclostyle stencil in that nine-pin printer. Instead of the letters that hit it on a typewriter, the needles would hit it and make the holes. The only thing was that the waste wax always clogged up the printer a bit. We had it borrowed from Ivan Havel, and once he was really angry at us for messing it up.

JŠ: Were those printers rare?

FS: They didn't exist here, one had to bring them from the West. We only had a half-format printer – like for receipts. When we did something, we had to do it in two columns and then glue the stencils together. So that was the first use.

But mainly, when the computer had that D-Text, which was a kind of precursor to T602 [Czech word processor]. Everything was in columns and the letters had an eight-hole form. The whole alphabet was made from that and that's how it printed. So we used this first to do typesetting. It could justify from the back, which you can never do on a typewriter. We played around with that a lot. Then you could also make larger letters and headlines on it. It could only do two different text sizes, but that was already progress. Then we realized that something could be drawn on it too, so I gave the stencil to the artists to draw something on it. So we had the matrix all patched up. We had columns on the computer and drawings in them. We did this for the first time in Vokno from 1986 (issue 11 – note JŠ).

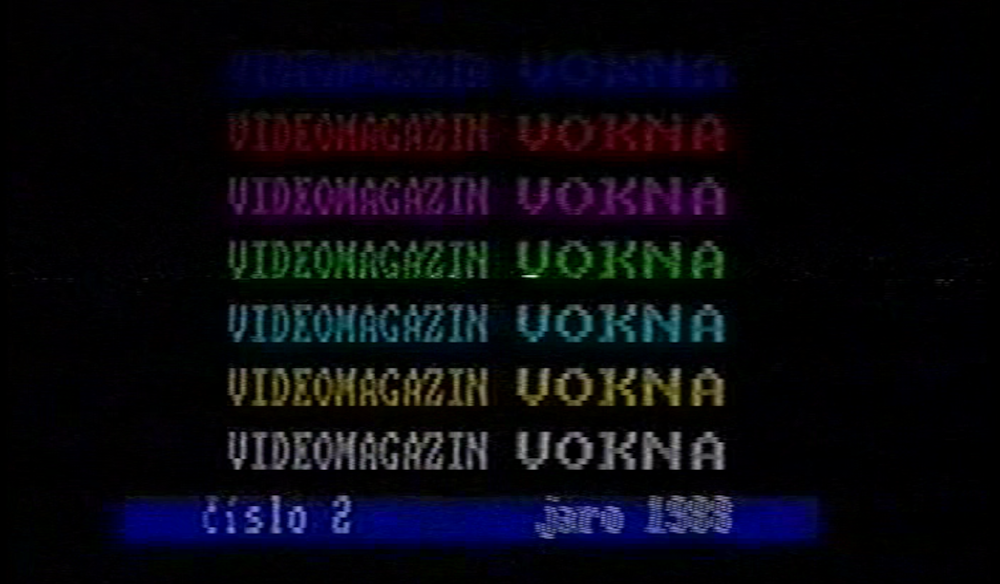

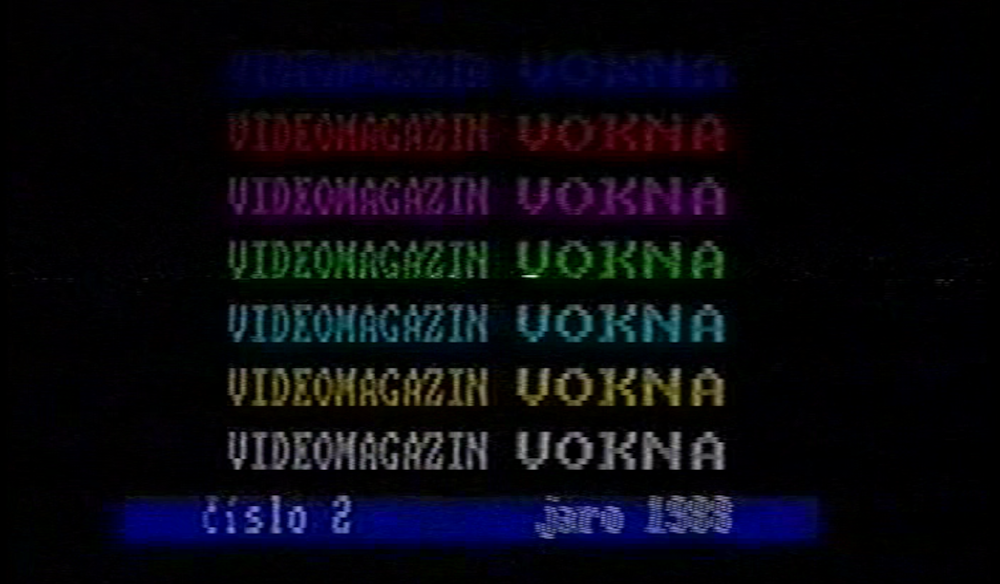

In the same year, video started to leak through. We had read about it before, but the money it cost was in completely different orders of magnitude than where we were operating. But as soon as Betamax arrived, both went down. To keep up, VHS also had to lower prices. At that moment, we grabbed onto it and started thinking about how to use it. We came to the idea that we would make a video magazine. The main thing that interested us in the media world back then was to be able to at least somehow start competing with television. That was the primary mainstream medium at the time, which seemed like it could do whatever it wanted with us – it had picture and sound. Suddenly even our opposition, underground magazine was able to produce picture and sound. To document our secret exhibitions. To be clear, during the samizdat era, we were unable to do color on anything. So artists could only show originals. But for someone to see a copy of a painting on the other side of the country – that wasn't possible. Photographs were terribly expensive, just once we put Slavík's photograph in Vokno – and it wasn't even pretty. Suddenly with video we were able to do color. Also the rewinding – you could work with it like a tape recorder. You could edit it. Those Beta machines were designed to enable dubbing. They knew that films were coming from abroad, so there was a dubbing button. We used that for commentary – we were able to lower the sound and do our own commentary. It was suddenly real studio work.

Vokno Video Magazine

Vokno Video Magazine

JŠ: To be able to edit, you had to have two of those machines – is that right?

FS: Of course. Not that we had them – we had to borrow them. We basically had one VHS available. One lad at Smíchov had bought one. Whenever we did it, we had to borrow a Beta and on that we made the master. Then we distributed from that Beta to VHS tapes. Distribution back then was more of an ongoing thing. We told our subscribers: Bring your own tape – we don't have the money to buy a tape. We had maybe ten of those tapes. One VHS tape cost six hundred crowns, and that was a third of my stoker's salary. Those were enormous amounts. Once we had picture and sound, we still needed subtitles. And that's where the Sinclair Spectrum comes in. Since there's a TV output, it was simple to send it to video instead of the TV. So we sent it to video and what would appear on the screen, we recorded. Now the task was to make a program that would scroll the letters. So in the

Vokno video magazine, the text scrolls. Our masterpiece was that our guys – Včelák and Anténa – made diacritics. So we were able to make titles in Czech.

Graphics for Vokno Video Magazine

Graphics for Vokno Video Magazine Graphics for Vokno Video Magazine

Graphics for Vokno Video MagazineThe only video magazine being made at the time was by Kyncl in London. He did titles directly with a camera – he had a titling device, but an English one. So he did titles in Czech, but without diacritics, like a telegram. They would say he was making telegrams.

We released two video magazines, but they were three-hour tapes. We released one every year. It wasn't for every issue of Vokno, because that would be too expensive. We released the very first Czech video magazine in spring 1987 and then the second in spring 1988. But by then the group around Ruml and Havel was doing Videožurnál. They had money, so they did it more often and had cameras. We were supported by Pavel Tigrid. We made that first video magazine completely without a camera. We only had a camera borrowed for one afternoon along with a cameraman – it was Honza Kašpar, who acted with Cimrman and also did Videožurnál. One afternoon on the Střelecký island [in Prague] I recorded the editorial and he filmed the animation of our jingle, which was made by our artist Martin Frynt. Filip Topol recorded jingles for us on the organ. We edited it on Beta and put Filip's organ below the titles.

The third use was organizational. The computer was able to produce cards. The distribution network of Vokno was so extensive that we needed to manage it by computer. We published Vokno and Voknoviny. Vokno came out once every six months and it was the thick one. But we needed to have much faster interaction with our readers, so we published the so-called Voknoviny. Ten printed pages and it came out every month. We sent it normally by mail. We had a distribution spider in the computer, and that computer could print all addresses on stickers. Our narrow printer was enough for that. So we printed the addresses like this and had to put them in the mail. But it couldn't be sent in bulk. I did that once and what I sent immediately got lost. At that time I traveled from Česká Třebová at night and had a winding route with almost 70 mailboxes, and so I put five at a time into mailboxes in various villages.

You also needed to see who had to pass it on to whom. It wasn't coming out of Prague in the shape of a sun; it was a spider. We gave it somewhere and that person passed it on. We sent Voknoviny to all the end recipients. But Vokno couldn't go by mail, it had to go hand to hand. Someone went to that address or had an acquaintance who studied in Prague and brought it. And we had to know how many to give him. He knew that from Pardubice he had to give it to Chrudim and so on. We sold Vokno, but we sent Voknoviny for free. Samizdat had its own economy. We made about 380 copies of Vokno and about 500 of Voknoviny.

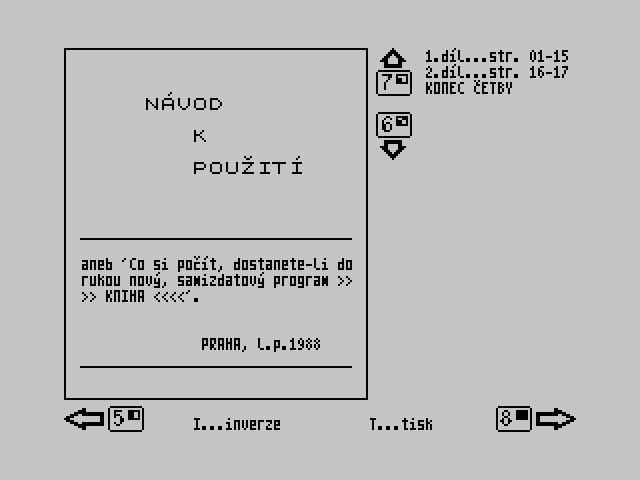

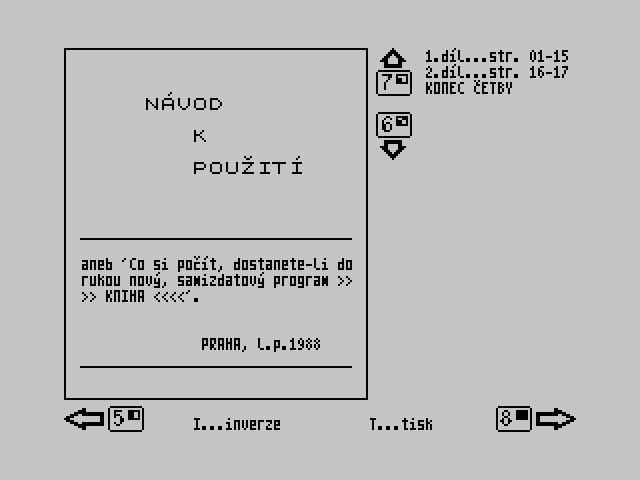

Then we had something like a Samizdat Research Institute and we were thinking about how we would do it in the future. There was an idea that samizdat would spread via computers. That we would release a tape among people with the whole magazine on it, and everyone would display it on their screen or print it on paper, as they wanted. This wasn't fully realized, but we had made a start. Jirka Včelák had gutted that D-Text somehow. He was a top IT guy for his time. He made a reading program out of D-Text, today it would actually be called an e-book program. We were going to always fill it with data that we had written. It was called the Kniha (Book) program. That was already an original product that worked. The Vokno cover was even there as graphics.

JŠ: Is that program archived somewhere?

FS: I definitely have the Kniha program somewhere. I still have fifty tapes at home with various programs on them. But first I have to start up the Spectrum to find it.

Kniha program loading screen

Kniha program loading screen Kniha program

Kniha programJŠ: Did you keep the tapes with subscriber lists hidden somewhere?

FS: The good thing about it was that tapes were easy to handle. I also had a paper distribution list where I had addresses sorted by regions and districts. (Shows.) I never had this at home, I kept it hidden and the cops never found it. But you need to be working with it. So I had to have it available and hidden at the same time. That was quite tricky. So I used the one I had on tape in D-Text for the labels. I had it recorded so that there was some music – the Beatles were there, I remember that. About five songs played and then in the gap there was that (imitates the sound of a tape on Spectrum) and that was the address book. I had the tape wrapped up and it was under the coal, I knew exactly where. When I needed it, I went to the shed, took it, chased away the kids who were playing some game, and started it up.

JŠ: What was your own relationship to computer games?

FS: I was absolutely thrilled by it, of course! Those computers in eighty-six, that was a blast! It was like this – one technical miracle after another was coming. The first was satellite. We sat for hours watching Western television. Then came video – we sat until three in the morning watching films. Then came the computer, so we sat until three in the morning at the computer. Not that we only played games, but we also played with the computer. We tested out what was possible to do with it, what all it could do. People exchanged programs on those tapes. The one to have more tapes was able to do more.

JŠ: Did you actively play games yourself?

FS: I played Jumping Jack. That was kind of our biggest hit at home. When my son started playing it better than me, I stopped playing. I also remember a text adventure about Egypt. How many grain silos you need to have to build a pyramid. I think it was called Hammurabi. I liked that too. Then there was this frog jumping out of a well. Anténa would play that all the time. And I sat down with it once – and since the biggest fool has the biggest luck, I jumped out of the well on the first try. And he was so pissed off! He had been playing it for several months and never jumped out anywhere. Of course we too played games, but that was just leisure time.

JŠ: Did you have any relationship to Svazarm?

FS: None. There were probably a lot of skilled people there, but because it was tied to security, to the police and the military, it was extremely suspicious to us and we were afraid of it. We were afraid we could run into trouble there. I have to say that at that time a community of people like that existed outside of Svazarm too – but it was all based on personal acquaintances, not through an organization. We would be afraid that someone would report us. After all, did take my computer away during a house search. We were radical even within the Charter, we were one floor lower. The punishment and the pressure from the StB on us was far more enormous.

JŠ: Did you know about anti-regime games like Indiana Jones on Wenceslas Square?

FS: It's possible something like that existed, but my story ends in February 1989, when they arrested me and I sat in prison until the revolution. I don't know the peak of eighty-nine. I was in custody in Hradec Králové and then serving my sentence in Horní Slavkov. Maybe Včelák or Anténa would know about it. They made things like this back then (shows

Voknoviny with Čuňas drawn on a computer), when I came back from prison. Husák gave amnesty to samizdat journalists after those round tables. So I returned on December 16th. And then we started on Atari. The guys just said we would go with Atari. That already had floppy disks. Later we got money from the Charter Foundation and bought PCs with that.

There's also another story connected to that. Václav Havel had a PC to write plays and so on. Now they did a house search at his place and took it. But the StB didn't have any computer wizard – just one. And he was away somewhere in Krivoy Rog, that was in Russia, where Czechs were building an oil pipeline. When he returned, they proudly showed him that they had seized Havel's computer during a house search. He rolled his eyes and said: Now get yourselves together, go back to Havel's place and also take the metal box. They only took the monitor and keyboard.

JŠ: Is this story verifiable in Havel's memoirs?

FS: I don't know, but I have an StB video recording from that house search, where the video focuses on the computer. I sometimes show that video during lectures. But I just know that story. After the revolution I worked at BIS, so I still caught those StB agents there.

On the internet edition of Vokno (recording 3):

FS: Some students then wanted to publish Vokno on the Internet, but it didn't work out at the time because we couldn't make Jirous write on a computer. I got a fairly expensive publishing program, but he needed to typeset it directly from some internet café. And he said: I can't do it, I won't do it. I told him: – Can you type on a typewriter? – Yes. – And can you make a phone call from a phone booth? – I can do that too. – Well, when you put that together, that's an internet café. That's where it fell apart. But they made me write an editorial for that internet edition. And so I wrote this poem:

When Martin Jirous in the Valdice prison

Was betting on the help of saints

I made myself a radio at Bytíz

And BBC brought me joy

If computers had existed back then

We wouldn't have had to go to jail

Father Pentagon and mommy CIA

Then gave birth to the Internet

No dictatorship will survive

The rise of IT technology

It's guranteed by its uncle

Cybershaman Bill Gates

End of interview  Vokno Video Magazine

Vokno Video Magazine